Below is a copy of my article, ‘My Year of Living Shamefully’, which was originally published in The Weekend Australian on 11/11/2021. My thanks to Literary Editor Caroline Overington for commissioning the piece and for permission to reproduce it.

My Year of Living Shamefully

by Michele Seminara

In the 1970s, poet John Forbes dubbed the Australian poetry scene “a knife fight in a phone booth”. Fifty years on, the phone booth is outmoded, but some in the insular poetry scene still wield knives, albeit on Twitter.

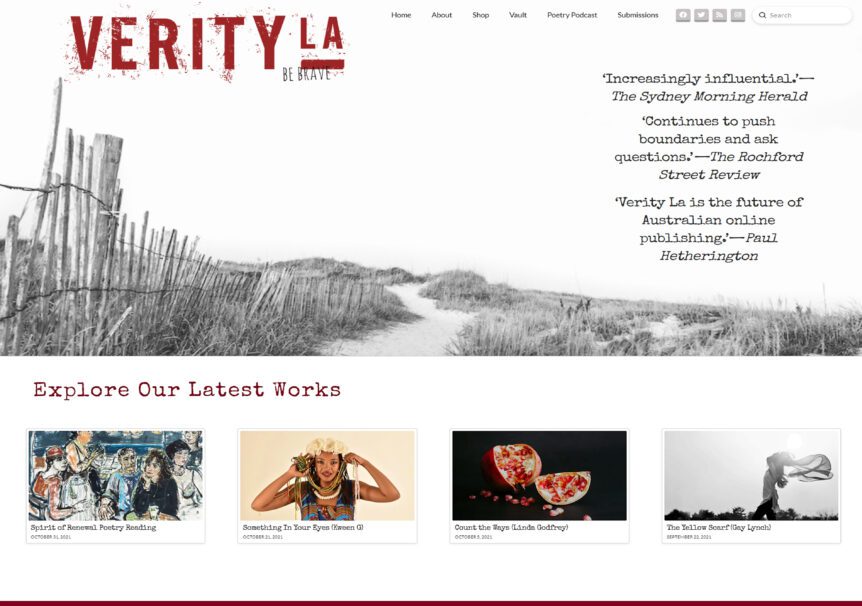

In 2015, I took over as managing editor of online creative arts journal Verity La. I had been raising three kids, but now the youngest was off to school, I was keen to rekindle my passion. By 2020, I’d recruited a volunteer staff of 19 editors (each working anywhere from a few hours a week to a few hours a year), was publishing 100 new pieces a year, and paying writers through a combination of grants, book sales and fundraising. I dedicated 20 hours a week to managing the journal and had eagerly established four new specialised writing streams – Discoursing Diaspora, Disrupt, Black Cockatoo and Clozapine Clinic – projects run by and for traditionally marginalised writers.

Exciting things were happening at Verity La, and while I didn’t expect lashings of thanks, neither did I see the backlash coming.

In May 2020, we published a story called “About Lin” by poet and academic Stuart Cooke. It was a challenging piece exploring the power imbalance in a sexual relationship between a white Australian male and a Filipina woman.

For nearly a month, it sat on the website without comment.

Then, on June 13, a poetry colleague who was also on the journal’s advisory board texted to say that “when it came out, I read it, and I thought it was racist, sexist and just not very good”.

She also said she wanted to “step away from the board”.

I was unsure how to respond. In the four weeks since About Lin had been published, I’d happily arranged to administer an arts grant for this colleague through Verity La, at her request, and we’d chatted many times. I was confused by her sudden change of heart toward the journal, and when she emailed her resignation the next day, I let her know that I valued her opinion and urged her to stay on.

To my dismay, she refused, saying the piece’s publication had led her to feel “unsafe as a woman and writer of colour”.

Unsettled, I revisited “About Lin”. I also sought feedback from a broad range of peer reviewers: had we been wrong to publish the story? I was open to taking it down, but since we’d only had one complaint, the board, after receiving advice, decided to keep it online, prefaced by a trigger warning and statement explaining we did so in the spirit of encouraging important conversations around themes of power, privilege, race, sexism and literary representation.

In retrospect, we might not have got it right, but I can say with hand on heart that it wasn’t from lack of caring or trying.

What happened next felt like an ambush.

On June 15, I received a call warning me that writers and editors from Verity La and the broader literary community were being informed I had dismissed my colleague’s concerns. Next, two Verity La editors, both poets, resigned in protest and publicised their stance on Facebook.

The stage was set, the community primed for outrage.

On June 25, I woke to an email from a group of Filipinx-Australian writers demanding we remove “About Lin”. Now we no longer had just one complaint; we had many. By the end of the day, the story was removed, and apologies issued.

Apologies used to be more straightforward affairs, given and taken in the spirit of human fallibility. Now, on social media, they’re linguistic minefields.

First, I apologised via email to the Filipinx writers and offered, by way of reparation, to commission five Filipina women to write stories of self-representation (an offer they declined). Next, I apologised publicly on Twitter, and when the first apology was found wanting, I issued another. Still the storm raged.

Panicking, I blocked some of the more vocal accounts, only to be accused of “silencing the voices of women of colour”. This wasn’t my intention, so I quickly unblocked them then apologised again. Privately, I also reached out via a mediator to the Filipinx writing community; nobody wished to talk.

Simultaneously, I was fielding distressed calls from Verity La staff who were being pressured to resign. One called to request their name be removed from our website after receiving more than 50 haranguing messages in one weekend. These volunteers, many of whom hailed from the very marginalised communities those bullying them claimed to care about, were being targeted for simply working with a journal that had published a story they had no hand in choosing. I took everyone’s names off the website.

My public shaming lasted for months and its digital footprint endures. Without proof, I was accused of “silencing” people, “erasing” them, “gaslighting” and “ignoring” them. Every night I woke panicked at 3am, drowning in self-censure. Psychologists agree nothing pains the human psyche as much as being shunned, and in the modern-day arena of social media, weaponised shame can be lethal.

Emails flooded in: other editors gleefully berating me, writers withdrawing their work from the journal, organisations uninviting me to judge poetry prizes, and worse, my publisher saying that since my former colleague had “made a point” of emailing to express her “concerns” over “my recent behaviour” they were postponing the impending publication of my book. I was gutted.

Then, on August 18, an “open letter” was circulated on social media demanding Create NSW defund the “racist, white supremacist organisation Verity La”. It elaborated on “the behaviour of its managing editor”, which had been “nothing but spiteful … including malicious, racist and sexist remarks … with online abuse levelled at writers of colour”. Again, no evidence was provided.

Surely, I thought, those who’d happily worked with me just weeks before would not believe it?

But I was missing the point: I had been tarred and feathered, and whoever dared stand with me would be too.

Unsurprisingly, few did.

Curled in a foetal position in bed that night reading the growing list of 250 signees – many of them colleagues and “friends” – I finally surrendered and decided to close the journal. Nothing was worth this much stress, not just to me but to my family.

Then something unexpected happened: the open letter disappeared. Perhaps there was some support out there, some way forward? In dribs and drabs, it came. An article appeared in The Australian, and another in The Spectator. The artistic director of Canberra Writers Festival, Jeanne Ryckmans, contacted me after coming under fire from some – you guessed it! – poets for the festival’s alleged “lack of diversity”. She was called “a right-wing, shit …who won’t engage with their literary community” and it was falsely claimed that she was part of an “all-white board” (Ryckmans is Eurasian).

On hearing my story, Ryckmans bravely stuck her head above the parapet, tweeting, “Bravo, Verity La. Happy to know you’re back”, and cited a quote from her late father, renowned writer and Sinologist, Simon Leys. In response, just days after the anniversary of Ryckmans’ father’s death, my former colleague tweeted a screenshot of his Wikipedia entry capped by the mocking comment, “I think it’s a quote from Daddy … Unfortunately he’s no longer around to speak for himself”.

Bewildered and distressed, Ryckmans called late at night, and I regretfully welcomed her to the poetry phone booth as she struggled to hold herself and her festival together amid the pandemic. We’ve since become firm friends.

A year on, I’ve cautiously begun to rebuild Verity La. I’m the only remaining editor and my chances of receiving funding to support the writing community have been destroyed. My former colleague, on the other hand, has received yet another grant to write her next book.

Rebuilding myself is likewise a work in progress. Having weathered the knife fight, I can now say that I’m no longer afraid to be judged or disliked and have grown a stronger spine. I’m also grateful for old and new friends who can make mistakes, learn, and disagree without cutting each other to shreds.

Yet I worry how others will cope in this unforgiving culture. As questions about freedom of expression challenge the publishing sector, onlookers are reluctant to call out bullying for fear of becoming the next target. I don’t blame them – I often wonder how I would have fared had I been younger or less robust. But we shouldn’t have to risk our health, livelihood, and sometimes our lives to bring about progress. Surely there’s a kinder way, if both sides are genuinely willing to forgive, dialogue and listen. The word poet comes from the Greek poietes, meaning “to make”. What sort of literary community do we wish to make? Whether “About Lin” should have been published or not, what has been achieved by Verity La’s demise, and who has benefited? Perhaps it’s time to lay down our weapons and find the courage and compassion to constructively wield our words.